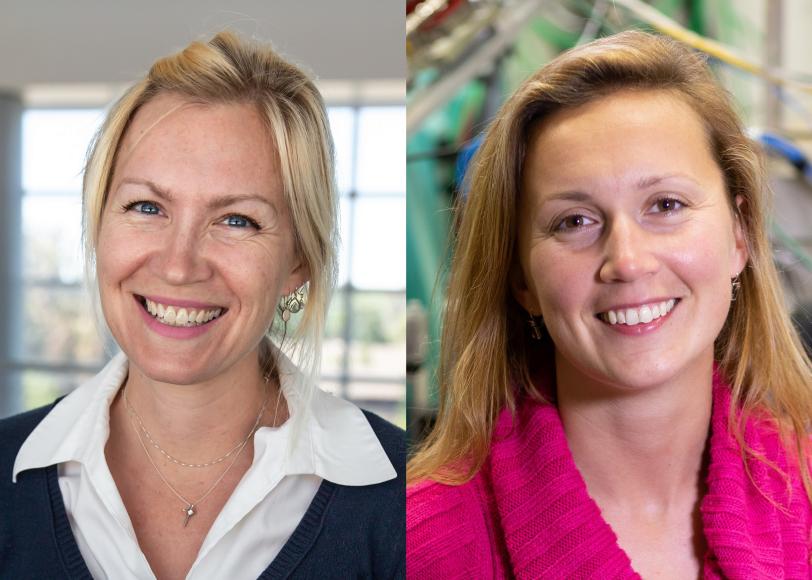

Arianna Gleason and Diana Gamzina receive DOE Early Career Research grants

The SLAC scientists will each receive $2.5 million for their research on fusion energy and advanced radiofrequency technology.

By Ali Sundermier and Manuel Gnida

Arianna Gleason and Diana Gamzina, staff scientists at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, will receive prestigious Early Career Research Program awards for studies in fusion energy and the development of next-generation radiofrequency (RF) technology. They are among 73 recipients selected from a large pool of university and national laboratory applicants, the DOE Office of Science announced today. Each will receive $500,000 per year for five years in support of their work.

Gleason will investigate extreme states of matter and how they might be harnessed for fusion energy, which one day could help address the world’s energy needs. Gamzina will study how materials behave when exposed to RF fields, which will lead to the development of improved materials for particle accelerators used in cancer treatments, novel RF sources for communication systems and more.

The grant program, now in its 10th year, is designed to bolster the nation’s scientific workforce by providing support to exceptional researchers during the crucial early career years, when many scientists do their most formative work, the DOE announcement said.

JoAnne Hewett, chief research officer and director of Fundamental Physics at SLAC, said, “The DOE Early Career Awards give promising young scientists the funding they need to reach their goals. Over the years it has been a highly successful program in launching spectacular careers. This is a significant accomplishment, and I give my sincere congratulations to these two outstanding SLAC scientists!”

Arianna Gleason: Putting the sun in a box

Gleason came to SLAC in 2018 from DOE’s Los Alamos National Laboratory, where she studied how iron behaves in the extreme conditions found in Earth’s core. Her interest in geophysics and planetary science developed during her undergraduate years at the University of Arizona, where she was part of a group called Spacewatch, tracking the paths of new asteroids and comets – including “Gleason,” an asteroid named after her.

In her graduate studies, however, she started using X-ray experiments to investigate planetary interiors and formation processes with the goal of better understanding how planets evolve.

“I became more interested in what these planetary bodies are made of and how that connects to other geologic features,” she said. “I transitioned from looking up through a telescope to looking down into a microscope.”

At SLAC, Gleason’s goal is to unravel the physics of materials in extreme conditions with the lab’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) X-ray laser. The Early Career Award will fund her investigations into fusion energy science.

“We want to figure out how to ‘put the sun in a box,’” Gleason says, “how to capture that same physics and optimize it as a clean energy source. If we could find a way to harness that energy, to generate these extreme states of matter and house them safely and effectively, it would make the world a better place.”

At the atomic level, materials that researchers might one day use in fusion energy reactors have instabilities and flaws. Gleason says it’s these flaws that make the materials simultaneously interesting and irritating. Their complexities directly influence how the material performs or behaves in the extreme conditions required for fusion, but large chunks of the physics needed to understand and control them are missing.

One of Gleason’s main focuses is called void collapse physics, where defects or imperfections in a material coalesce to form voids. This process affects how materials degrade or fail, but it’s not fully understood. Through her research, Gleason hopes to use LCLS to follow the voids, mapping conditions like temperature and pressure to elucidate the process at extremely small and fast scales.

“Part of my focus is to look at the fundamental processes of void collapse and connect them directly to the formation of instabilities,” Gleason says. “To do this, I’m pulling in talent from areas outside of my expertise from SLAC, the University of Rochester, DOE’s Los Alamos and Lawrence Livermore national labs and Stanford University. Our goal is to use LCLS and other light sources to make 3D movies of void collapse, with sensitivity to pressure, temperature and structure.”

What they learn will feed models that could show researchers how to engineer the voids and how materials could fail in a way that makes them more effective and safer to use. This would enable new battery technology and stronger, optimized materials for clean energy from fusion or for reentry vehicles that face extreme conditions when they come back into the atmosphere from space.

The Early Career Award, Gleason says, will allow her the freedom to work with her collaborators and tinker with her experiments, finding the elusive shared space where all the disparate experimental approaches, from shock compression to imaging, overlap to enable innovation.

“The ability to pour your heart and soul into experiments is a remarkable thing,” Gleason says. “You might not get something to work on the first try, but learning from your failure and trying again is where science lives and discoveries happen. The Early Career Award will give me the scientific freedom to focus on an important problem and learn new physics with each attempt to understand it. My hope is that what we learn will engage other scientists, sparking collaboration and bleeding into other experiments.”

Diana Gamzina: Improving X-ray technology using X-rays

Diana Gamzina came to SLAC from the University of California, Davis, where she earned bachelor’s degrees in mechanical engineering and materials science, a master’s degree in mechanical engineering and a PhD in mechanical and aerospace engineering. At Davis, she also worked as a principal development engineer, focusing on R&D of high-frequency RF sources. She joined SLAC’s Technology Innovation Directorate as a staff scientist in January 2017.

She will use her award to study how powerful RF radiation causes materials to fail. The ultimate goal: develop materials that better withstand radiation damage.

RF technology is at the heart of a number of important applications. RF sources, for example, are key components of modern communications systems on Earth and in space. And in particle accelerators, RF fields boost the energy of particle beams used in “super-microscopes” that reveal nature’s fundamental building blocks, in medical devices for radiation cancer therapy, and in ultrabright X-ray light sources like LCLS that “film” atoms as they rapidly jiggle in materials.

Making RF devices smaller and more powerful could shrink accelerators, make radiation therapy more effective in killing cancer and make it easier to fit powerful RF emitters into satellites, for instance. But packing more power into smaller and smaller RF structures can break down materials.

“A large portion of my work has been trying to develop RF devices that fit in the palm of your hand but are still powerful enough for potential applications,” Gamzina said. “Before we can be truly successful, we need to understand what makes materials fail under high RF power densities.”

Researchers have been asking this question for many, many years, she said, and until now nobody has been able to determine what exactly happens to the structure of materials on a microscopic scale when they degrade under those conditions. Gamzina’s Early Career Award project aims to change that.

In a first step, she will use a new, unique RF-pump X-ray probe instrument at SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsouce (SSRL) to look at microstructural changes in materials hit by RF pulses. Then, in collaboration with Lawrence Livermore lab, she’ll develop theoretical models based on the SSRL data to explain why materials respond in certain ways to RF radiation. The goal is to find new ways of making materials 10 times more robust in the face of high-power RF fields.

The studies will focus on copper and niobium, metals that are widely used for RF applications. At SLAC, a 2-mile-long linear accelerator made of copper and operating at room temperature has been instrumental for a long, successful research history. Today, one-third of that linac drives the generation of X-rays in LCLS. Another third is being replaced with a superconducting accelerator using niobium components that will operate at about the same temperature as outer space and enable the LCLS-II upgrade to fire X-rays up to a million times per second.

“Looking at two materials sounds easy, but it’s actually much more challenging than it sounds,” Gamzina said. “There isn’t just one form of copper or one form of niobium. There are many variations for both metals. Copper can have many different microstructural states that affect its behavior, and the superconducting properties of niobium depend on its surface properties, impurities and so on.” For the niobium work, Gamzina will collaborate with DOE’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, one of the national labs building superconducting accelerator structures for LCLS-II.

What excites her most about this research is that it’s very complex, bringing multiple aspects of physics and engineering together to explain a fundamental phenomenon in materials science. SLAC is a great place to make all these connections, she said.

“We’re a leader in the development of RF sources, we have extremely strong expertise in copper accelerators and we’re expanding our expertise in superconducting technology. And then we have a tool like SSRL, which uses a lot of that technology and expertise to generate powerful X-rays,” she said. “My project connects these things: We’ll be using our own tool – SSRL – to better understand and improve the devices – RF sources and accelerator structures – that make our tools possible in the first place.”

LCLS and SSRL are Office of Science user facilities.

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit energy.gov/science.